Modules | |

| Error Codes | |

Classes | |

| struct | lpf_args_t |

| struct | lpf_machine_t |

Macros | |

| #define | _LPF_VERSION 202000L |

| #define | _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY 202000L |

| #define | _LPF_EXCLUSIVE_MEMORY 202000L |

Typedefs | |

| typedef void * | lpf_t |

| typedef void(* | lpf_func_t) () |

| typedef void(* | lpf_spmd_t) (const lpf_t ctx, const lpf_pid_t pid, const lpf_pid_t nprocs, const lpf_args_t args) |

Variables | |

| typedef | lpf_pid_t |

| const lpf_args_t | LPF_NO_ARGS |

| typedef | lpf_err_t |

| typedef | lpf_init_t |

| typedef | lpf_sync_attr_t |

| typedef | lpf_memslot_t |

| typedef | lpf_msg_attr_t |

| const lpf_t | LPF_NONE |

| const lpf_t | LPF_ROOT |

| const lpf_init_t | LPF_INIT_NONE |

| const lpf_sync_attr_t | LPF_SYNC_DEFAULT |

| const lpf_msg_attr_t | LPF_MSG_DEFAULT |

| const lpf_pid_t | LPF_MAX_P |

| const lpf_machine_t | LPF_INVALID_MACHINE |

| const lpf_memslot_t | LPF_INVALID_MEMSLOT |

Detailed Description

Semantics

The C language is well known for its speed when the programmer does everything right, as well as for its Undefined Behaviour (UB) when the programmer did something wrong. The same holds true for this API: each function has well-defined behaviour, provided that a set of preconditions are satisfied; when any precondition is violated, a call will instead result in UB. We capture these semantics in natural language as well as formal semantics. Behaviour of a function comprises, given the input state and the function parameters, the following aspects:

- functional behaviour: definition of the resulting state.

- cost model: the wall clock time to complete communications.

- computational costs: definition of the asymptotic run-time of a function call.

Functional behaviour

For each LPF primitive defined in the core API, a strict set of rules defines defines the behaviour of an implementation. If a call to a primitive violates its preconditions, then UB will be the result. If, during a call to an LPF primitive, an implementation encounters an error, it will behave as defined for the encountered error condition (usually meaning the primitive shall have no effect) and return the associated error code.

Cost model

To the designer of an immortal algorithm, predictability of the LPF system is just as important as its functional behaviour. Precisely specifying costs for each function individually, however, would restrict the implementation more than is necessary, as well as more than is realisable within acceptable cost.

Regarding necessity, and for example, LPF defines nonblocking semantics for RDMA communication. Therefore, an implementation could choose to overlap communication with computation by initiating data transfers at each call to lpf_get() or lpf_put(), without waiting for an lpf_sync(). On the other hand, another implementation could choose to temporally separate communication from computation by delaying the initiation of data transfers until such time all all computation globally has completed. LPF allows both (and more), yet strives to assign an unambiguous cost as to the completion of the communication pattern as a whole, and in isolation from any computational cost: the LPF, as a communication layer, only assigns a precise cost to communication, not computation.

In line with the above, instead of specifying the cost for each function individually, LPF specifies the total runtime costs of communication during groups of independent supersteps. If no extensions to the core API are in use, the BSP cost model specifies the wall-clock time of all calls to lpf_put(), lpf_get(), and lpf_sync() in a single superstep; see The BSP cost model for more details. An LPF implementation may enable the alternative choice of any relaxed BSP model. LPF also allows for probabilistic superstep costs that may futhermore be subject to SLAs over many executions of identical communication patterns. Finally, a call to any LPF primitive has asymptotic work complexity guarantees. These constitute the only guarantees that LPF defines on computational cost.

Through all these guarantees, probabilistic or otherwise, LPF allows for the reliable realisation of immortal algorithms.

Communication

LPF follows the BSP algorithmic model in that computation and communication are considered separately, and that a computation phase and a subsequent communication phase constitute a superstep. The BSP cost model, as well as any BSP-like cost model, exploits this separation to assign a cost to the execution of a given communication pattern. Note that a run-time system may overlap computation and communication during actual execution as long as doing so does not conflict with the chosen BSP or BSP-like cost model.

A conceptual description of the communication model

We sketch here an abstraction that applies to all BSP-like models of parallel computation, the so-called bag of messages, and how this interacts with the core API.

All code written using LPF execute in the compute phase. This means all calls to lpf_get() and lpf_put() register communication requests to the runtime, which may or may not immediately initiate communication. A call to lpf_sync() ends the current computation phase and returns when the LPF process which called lpf_sync() can safely continue with the next superstep.

A communication request thus registered during a computational phase is a triplet \( ( s, d, b ) \). It consists of:

- a source memory area identifier \( s \) that encapsulates a process and a memory address on that process,

- a destination memory area identifier \( d \) that encapsulates a process and a memory address on that process, and

- the number of bytes \( b \) to copy.

Any call to lpf_put() or lpf_get() is translated into such a memory request, after which the memory request is put into a conceptual bag of message requests \( M \). A communication request, once executed, is removed from \( M \). A subsequent call to lpf_sync() guarantees that all messages \( ( s, d, b ) \in M \) are executed and removed from \( M \). Any given process is safe to continue whenever, for all remaining messages \( (s,d,b) \in M \):

- \( s \) does not reside on the given process, and

- \( d \) does not reside on the given process.

Unbuffered Remote Direct Memory Access

An implementation may, at any time before and during the call to a subsequent lpf_sync(), process any part of any message request already in \( M \). Messages in \( M \) may overlap in their destination memory area: these result in write conflicts. The conflicted destination memory areas, after a subsequent call to lpf_sync(), must match the result of a serialisation of the messages in \( M \). Because LPF does not define which serialisation, this conflict resolution is called arbitrary-order and is well-known from literature on the CRCW PRAM model. While the end result must match a serialisation, an implementation is not required to actually serialise communication– implementations are, in fact, not even allowed to serialise for more than one processes since doing so would violate the BSP cost model, while relaxed BSP models are only allowed to improve this default cost.

While it is legal to define global communication patterns with write conflicts, some illegal patterns remain. Specifically, a global communication pattern \( M \) is illegal when

- there exist any two message requests \( r_0=(s_0,d_0,b_0) \) and \( r_1=(s_1,d_1,b_1) \), \( r_\{0,1\} \in M \) such that \( s_0 = d_1 \) or \( d_0 = s_1 \).

Violating this restriction results in undefined behaviour.

Recall that communication patterns in LPF are registered during the computational phase of a superstep. User code, during a computational phase, shall not address (except via LPF primitives):

- a source memory area after it was locally designated as such after an lpf_put().

- a destination memory area after it was locally designated as such after an lpf_get().

- a source memory area that is designated as such by a remote lpf_get() requested during the same superstep.

- a destination memory area that is designated as such by a remote lpf_put() requested during the same superstep.

Violating any of these restrictions results in undefined behaviour.

Using relaxed BSP models

BSP-like models may be employed via dedicated implementations of the LPF core API and/or via extensions to the LPF core API. LPF specifies in which ways the core API can be extended to ensure any algorithm making use of extensions still functions using the standard semantics. LPF additionally requires that implementations ensure that the overall time spent communicating does not exceed the cost defined by the BSP cost model– that is, implementations may only define extensions and modify the cost model if the default cost remains a valid upper bound to the actual cost.

Application development support

To make LPF available for practical use, it must be easy to retrofit existing codes with algorithms implemented using LPF.

SPMD section confinement

Ideally, an application developer who makes use of a third-party binary module should never need to make any changes to his code when that module updates to make use of LPF.

To meet that requirement this API specifies the lpf_exec() function. It takes as argument an SPMD callback function and an LPF context, which, in turn, must always be passed as the first parameter to every other LPF SPMD function. It also provides the process ID and the total number of processes involved in its current SPMD run, and provides access to input and output arguments to each process individually.

The lpf_exec() function can be called from anywhere in the program, even from within an SPMD section. It will guarantee that the callback function is executed in parallel using, at most, the specified number of parallel processes.

Example:

If existing code already has spawned multiple processes using a framework other than LPF, then calling lpf_exec() will not re-use those pre-existing processes to run the requested LPF program; rather, it may instead spawn additional new LPF processes per pre-existing process, and then have each pre-existing process run its own instance of the requested LPF program.

If this is not intended, and the given LPF program should instead re-use the pre-existing processes and not spawn new ones, the lpf_hook() should be used instead.

SPMD section structure

Besides SPMD section confinement there are no other features that help structuring SPMD program text. Although the C language supports structured programming, this is only limited to sequential, Von Neumann, machines. In particular, it is not aware of the parallel programming rules that the use of LPF requires. Take as example the lpf_sync() primitive, which breaks any encapsulation:

(This code ignores error codes for simplicity.)

On first sight, the communication that is performed in the final lpf_sync() looks balanced. However, notice the call to black_box() which is passed the LPF context. It can be

which means the final lpf_sync() in foo will be a \( (p+1) \)-relation, where \(p\) is the number of processes. On the other hand, the black box could read

which would mean that the final lpf_sync() in foo would be a \( 2 \)-relation. Hence to understand the effect and performance of a lpf_sync(), complete knowledge of all SPMD code is required.

To enable the design of ‘black boxes’ (libraries) on top of LPF that do not require their users to track the use of LPF primitives with all libraries, LPF defines the lpf_rehook(). This primitive starts a new SPMD section within an existing one, mapping existing LPF processes to new ones on a one-to-one basis, providing a new context that is disjoint from the older one. This allows the definition of LPF libraries that take input and output through the standard lpf_args_t structure.

Note that this is the exact same mechanism LPF defines to simplify the integration of LPF algorithms from arbitrary external software via lpf_exec() and lpf_hook().

Nevertheless, some higher-level libraries that require tight integration by LPF algorithms, may opt to expose explicit LPF contracts for users to track. This enables best performance by not requiring many calls into the encapsulation-friedly lpf_rehook(), and make sense, e.g., for a collectives library.

Higher-level libraries that provide relatively heavy computations, in contrast, would do well to benefit of the lpf_rehook(). For example, a library designed to compute large-scale fast Fourier transforms in parallel would hide any overhead from encapsulation by lpf_rehook().

Finally, one may envision higher-level libraries that completely hide the LPF core API. LPF comes bundled with one example of this, namely, LPF BSPlib API Reference Documentation.

Scheduling and LPF

The LPF foresees four fundamentally different ways of executing an SPMD LPF program:

- lpf_exec(), which, given a sequential single-program context and given resources, starts a requested LPF program. The lpf_exec() hence creates and manages new processes to begin a new SPMD section, then makes sure the requested program is callable from each of the newly spawned processes, and then finally starts the requested program.

- lpf_offload(), which also starts from a sequential environment to start a requested LPF program. Unlike lpf_exec(), an offload does not yet have control over the resources necessary to execute the requested program. The lpf_offload() hence first performs resource allocation as well as some form of job scheduling (if the pool of resources is shared). After receiving a set minimum of dedicated resources, the offload will then spawn a single sequential program on one of the given resources, which will finally start the requested LPF program by a call to lpf_exec().

- lpf_hook(), which, given an existing external parallel environment, starts a given LPF program. The same program must be called from all processes. Via the lpf_hook(), LPF will temporarily take control of the external process to execute the requested SPMD program.

- lpf_rehook(), which, given an existing LPF context starts a given LPF program using a new LPF context. The same program must be called from all existing LPF processes.

This specification only defines the lpf_hook(), lpf_exec(), and lpf_rehook(). It allows for the lpf_offload() as an implementation-defined extension.

Runtime-error handling

A runtime error encountered by any third party library should never simply abort the entire application program. Likewise, calling lpf_exec() from within a larger user application should never halt the entire program without providing the opportunity to the top-level program to mitigate any errors encountered.

Runtime errors arise when a necessary and expected assumption about the system has not held true. E.g., an implementation could reasonably assume that memory necessary for buffer resizing, such as necessary for the lpf_resize_message_queue(), would normally succeed. If the user provides an unrealistically high value, however, or if the system is under unusually high memory utilisation pressure, this assumption is violated. In such cases, LPF returns an error code that allows for user mitigation of the problem: for example, the caller may opt to lower the amount of communications required (e.g., at the cost of extra supersteps) or may free non-critical memory and retry the same resize call again.

Runtime errors are communicated through return values. The special type for return codes is lpf_err_t, which is therefore the return type for all LPF functions. All error conditions and their coinciding error codes are specified in this document. One error code that all functions have in common is LPF_SUCCESS which means that the function executed the normal course of action. An implementation may define additional specific error codes for specific functions, though any high quality implementation minimises the number of error codes a user would have to deal with.

Sometimes errors happen that are assumed to be so rare that it is acceptable to terminate an LPF program immediately. Still, the application must have the opportunity to log the failure and/or seek end-user advice on how to proceed. For example, an LPF algorithm employed within a traditional HPC environment need not tolerate a suddenly-unplugged network cable, yet should inform its user when such a catastrophic network failure occurs. For this reason, the LPF defines the non-mitigable LPF_ERR_FATAL error code. When an LPF process encounters this error code, it enters a so-called failure state which guarantees the following and the following only:

- any subsequent lpf_sync(), lpf_rehook(), and lpf_exec() will return LPF_ERR_FATAL;

- any subsequent call to lpf_hook() from hence onwards incurs implementation-defined behaviour;

- the call to lpf_exec(), lpf_hook(), or lpf_rehook() that spawned the current SPMD section will return LPF_ERR_FATAL;

- other processes in this SPMD section may enter a failure state at any subsequent call to lpf_sync();

- any other process must enter a failure state during any superstep which requires data to be communicated from any LPF process already in a failure state.

All calls to any other LPF functions not mentioned in the above may return LPF_ERR_FATAL. If they do not, they shall function as though the process were not in a failure state.

A failure state is a property of an LPF process– LPF does not define a global (error) state. This allows for the lazy handling of failed processes, thus reducing communication and synchronisation requirements when no process is in a failure state.

- Note

- Another way of thinking about failures states is that after a process receives LPF_ERR_FATAL, all subsequent calls to LPF functions become no-ops. A program that would ignore LPF_ERR_FATAL error codes hence will not bring the library in undefined state. It will, however, run the risk of messages not being delivered, which might break data structure invariants in the user program. For that reason, error codes of the functions lpf_exec(), lpf_hook(), lpf_rehook(), and lpf_sync() should always be checked.

There are no checks for programming errors. While it never makes sense to execute a communication request that writes outside of any registered memory area due to overflows, for example, checking for such conditions would degrade performance significantly– not just within local computation phases, but also by increasing h-relations during communication phases. Therefore, the LPF core API ignores such programming errors entirely, instead clearly specifying what actions consititute programming errors and furthermore defining when such errors will cause undefined behaviour. An implementation, however, may elect to implement a debugging mode that does include run-time checks for programming errors to simplify debugging.

Macro Definition Documentation

◆ _LPF_VERSION

| #define _LPF_VERSION 202000L |

The version of this LPF specification. All implementations shall define this macro. The format is YYYYNN, where YYYY is the year the specification was released, and NN the number of the specifications released before this one in the same year.

◆ _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY

| #define _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY 202000L |

An implementation that has defined this macro may never define the _LPF_EXCLUSIVE_MEMORY macro.

If this macro is defined, then 1) if an SPMD section is created using lpf_exec, then the process with PID 0 shall have the same memory address space as the process that made the corresponding call to lpf_exec; and 2) if an LPF SPMD section is started using lpf_hook, then the memory address space of the process does not change from that of prior to the call to lpf_hook.

- Warning

- Truly portable LPF code does not rely on the existence of this macro. Within such compliant code, information between processes is only passed via lpf_args_t, lpf_put, or lpf_get.

◆ _LPF_EXCLUSIVE_MEMORY

| #define _LPF_EXCLUSIVE_MEMORY 202000L |

An implementation that has defined this macro may never define the _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY macro.

If this macro is defined, then SPMD processes started using lpf_exec or lpf_hook will never share the same address space. Some architectures require this, as do some LPF implementations.

- Warning

- Truly portable LPF code does not rely on the existence of this macro. Within such compliant code, information between processes is only passed via lpf_args_t, lpf_put, or lpf_get.

Typedef Documentation

◆ lpf_t

| typedef void* lpf_t |

An LPF context.

Primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t shall require a valid LPF context. Such a context can be provided by LPF_ROOT, or can be passed as a parameter of lpf_spmd_t as called by an implementation, via a preceding call to lpf_exec or lpf_hook. Using any other instance of lpf_t shall lead to undefined behaviour.

- Thread safety

- A call to any LPF primitive that takes an argument of type lpf_t shall be thread-safe if

- each individual thread makes such calls using only the lpf_t instance that was provided as a lpf_spmd_t parameter provided via lpf_exec() or lpf_hook().

Thus all LPF primitives are safe to concurrently call from different LPF processes, as is reasonable to expect. If a single process spawns multiple threads, however, this specification does not require the primitives be thread safe.

- Note

- An implementation may nonetheless choose to make all LPF primitives thread safe, but a user relying on such an extension

- is writing non-portable code, and

- loses performance due to locking on internal data structures of lpf_t.

- Communication

- Object of this type must never be communicated.

- Note

- This specification only prescribes that the state can be fully defined by a pointer to a data structure, but does not prescribe any restriction on how this data structure should be implemented.

◆ lpf_func_t

| typedef void(* lpf_func_t) () |

The type of a function symbol that may be broadcasted using lpf_args_t, via lpf_exec and/or lpf_hook.

- Note

- An implementation based on, e.g., UNIX processes, has to put in effort to translate a specific function at a root process into the correct matching function at a remote process; function addresses might not match across UNIX processes, after all.

◆ lpf_spmd_t

| typedef void(* lpf_spmd_t) (const lpf_t ctx, const lpf_pid_t pid, const lpf_pid_t nprocs, const lpf_args_t args) |

This is a pointer to the user-defined LPF SPMD program.

A user will supply his or her program to the LPF implementation as a plain C function with the prototype as defined by this lpf_spmd_t type.

- Parameters

-

[in] ctx The LPF context data. Each process that runs the SPMD program gets its own unique object which it can use to access the LPF runtime independently of the other processes. [in] pid The process ID. This is a value \( s \in \{ 0, 1, \ldots, p-1 \} \) that is unique amongst the \( p \) LPF processes involved with the SPMD section. [in] nprocs The number of LPF processes \( p \) involved with the SPMD section. [in,out] args The program input and output arguments corresponding to this LPF process; lpf_exec() will only communicate input and output from and to process 0. Other processes will receive args with lpf_args_t.input = lpf_args_t.output = NULLand lpf_args_t.input_size = lpf_args_t.output_size = 0. lpf_hook(), on the other hand, allows each LPF process to be assigned a different set of input/output arguments based on the process ID pid.

- Note

- The argument ctx is defined const because lpf_t resolves to a pointer type.

- Communication

- Objects of this type must not be communicated.

Function Documentation

◆ lpf_exec()

| lpf_err_t lpf_exec | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| lpf_pid_t | P, | ||

| lpf_spmd_t | spmd, | ||

| lpf_args_t | args | ||

| ) |

Runs the given spmd function from a sequential environment as SPMD program in parallel on a BSP computer and waits for its completion.

The BSP computer is given by ctx and must be be the current active runtime state as are provided by lpf_exec() or lpf_hook(). When neither call is in effect, an implementation usually provides a LPF_ROOT runtime state, representing the master process, for the purpose of running SPMD programs. Alternatively, lpf_hook() can be used to run SPMD programs.

The SPMD program spmd will be executed using P LPF processes. If lpf_machine_t.free_p, as reported by lpf_probe(), is smaller than P, the number of LPF processes will be equal to lpf_machine_t.free_p. If P is less than lpf_machine_t.free_p, then at least one of the LPF processes will be assigned more than one processor. Such LPF processes may use subsequent calls to this lpf_exec() primitive to make use of the extra processors assigned to them.

To pass input to the SPMD section and retrieve its output results, the args parameter can be given a lpf_args_t object with nonzero lpf_args_t.input_size and lpf_args_t.output_size while pointing lpf_args_t.input and lpf_args_t.output to appropriately sized memory areas. lpf_exec() will make sure that LPF process 0 will get the contents of the input memory area via a lpf_args_t object as well. Also, lpf_exec() will provide an output memory area to the SPMD program as large as is provided to lpf_exec() itself to retrieve the output. Finally, to support dynamic polymorphism, the lpf_args_t object can be given an array with function pointers which the runtime will broadcast and translate to local memory addresses.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified, and should not be relied on. Other primitives that take a lpf_t argument have similar thread safety properties; see lpf_t for more information.

- Note

- When interested in using existing threads to participate in running the same LPF program, consider using the lpf_hook() primitive

- Neither lpf_exec(), lpf_hook(), nor lpf_rehook allocate any space for memory slots and message queues before executing the spmd function, which effectively means that a call to lpf_resize_memory_register() should always precede the first call to lpf_register_local() or lpf_register_global(), and that a call to lpf_resize_message_queue() should always precede the first call to lpf_put() or lpf_get() in the spmd function.

- When application code encounters an error condition during execution of the spmd function, it is always possible to return from it directly. However, in case not all processes called lpf_sync() the same number of times, the runtime will enter a failure state and lpf_exec() will return LPF_ERR_FATAL. This mechanism is necessary in the case that, for example, the first call to lpf_resize_memory_register() yields LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY, so that there is effectively no way to coordinate the abortion of the spmd function. Returning from the spmd function at an arbitrary point during execution is not always safe, since the application code may have scheduled messages that origin or target memory regions in its stack frame.

If _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY is defined, the call to the given spmd function will be made from the same memory address space as the current call to lpf_exec. If _LPF_EXCLUSIVE_MEMORY is defined instead, only the data passed through args will be guaranteed to be available when the call to the given spmd function is made.

- Note

- An implementation with _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY can thus be passed a lpf_t object from a second LPF implementation. Calls can then be mixed as long as the conditions on thread safety of the lpf_t are never violated. An MPI-based LPF can thus be used to spawn N MPI processes using lpf_exec, each of which can then execute another lpf_exec using a POSIX Threads based LPF to spawn M threads. This allows for explicit multi-level programming of a \( MN \)-core multi-node multi-core machine, and allows for the relatively easy design of a portable Multi-BSP layer.

- Parameters

-

[in] ctx The current active runtime state as provided by a previous call to lpf_exec() or lpf_hook(), or, if none of the those have happened before, LPF_ROOT. LPF_ROOT may only be used if there is a master LPF process, otherwise use lpf_hook(). [in] P The number of requested processes. [in] spmd The entry point of the SPMD program. [in,out] args A memory area with input for process 0 and a memory area to store its output.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When the requested LPF SPMD section was successfully started and has exited.

- LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY When the system could not start a new SPMD section due to memory allocation failures. The program can proceed as though the call to this function had never happened.

- LPF_ERR_FATAL When not all processes called lpf_sync() the same number of times or when the library encountered an unrecoverable error during execution of the spmd section.

- Note

- On an LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY error, no ghost processes and no memory leaks are allowed. If an implementation cannot guarantee this, then the LPF_ERR_FATAL error code should be returned instead.

- A high quality implementation may make any data written to lpf_args_t.output by process 0 available to the calling process.

- BSP costs

- None (for the spmd function called, see The BSP cost model).

- Runtime costs

- In addition to the total BSP cost and compute time required to execute the user-defined SPMD program, the overhead of calling lpf_exec at entry is \( \mathcal{O}( P + (a+b)g + l ) \), where \( g, l \) are the BSP machine parameters, and \( a, b \) equal the lpf_args_t.input_size and lpf_args_t.f_size fields of args, respectively.

- Upon exit of the spmd function the overhead of this function is \( \mathcal{O}( ag + l ) \), where \( a \) equals the lpf_args_t.output_size field of args.

- Note

- A good implementation will achieve \( \mathcal{O}( P + g + l ) \) of total overhead if no process replication is employed.

-

Do not use the lpf_exec() args I/O mechanism to transmit significant amounts of data; if this is required, consider using dedicated parallel I/O mechanisms. The lpf_args_t arguments are intended as a mechanism to pass program control flows, for instance, just like the C-style

argcandargv.

- See also

- The BSP cost model.

- Implementation hints

- A distributed memory implementation (e.g. MPI) can be done in two ways:

- The code runs sequential as one process until it encounters the lpf_exec() command. Then it looks up the name of the symbols to which the function pointer points. It forks & execs mpiexec with a specialized executable that links dynamically to the executable again with dlopen and executes the function pointer on all processes. Potentially it could be made to work with a job scheduler so that the sequential program runs on a normal workstation while the parallel computation runs on a cluster, although this behaviour is more reminiscent of a lpf_offload function.

- The process is started immediately P times (e.g. on a cluster via job scheduler). All processes except process 0 will start waiting. Process 0 runs as normal until it encounters the lpf_exec() function. It looks up the name of the address of the given function pointer and resolves this to again a function pointer on the other processes, or it assumes that the function pointer will have the same value on all processes (without ASLR). This function is then executed on all processes. When it returns all processes except 0 will resume waiting again and process 0 will continue the normal course of the program.

- Rationale of parent-children communication

- The issue how to communicate between the normal program and the SPMD program is non-trivial. Several options were explored:

- The BSPlib approach where the parent process shares the same memory address space with process 0. Communication between parent and process 0 happens through global variables. This was rejected, because it is doesn't work in a fault-tolerant LPF runtime where processes are replicated. Furthermore, global variables are evil and should be avoided whenever possible.

- Communicate nothing. This is useless as any sensible communication will need to get its input from somewhere and should give a result back.

- Broadcast input from the parent to the LPF processes and reduce or gather their output to the parent again. Broadcasting a single value is fine, although it will not be high-performance in general, because there are use-cases where some LPF processes don't need (the same) input. In that case, the initial h-relation is larger than necessary. In the output direction, defining a reduction operator can be quite complicated. Alternatively, a gather operation could be used to retrieve the output, which will, however, need \( \mathcal{O}( P ) \) memory, which may be prohibitive.

- Scatter & gather an array to and from LPF processes. This will require \( \mathcal{O}( P ) \) memory on the parent process. For high number of processes this is too much.

- Send and receive only to and from process 0. This only needs a constant amount of memory. From a scalability perspective, this seems to be the best compromise between usabilty and performance. In the worst case, two extra supersteps will be necessary to communicate input and output data to the other processes.

◆ lpf_hook()

| lpf_err_t lpf_hook | ( | lpf_init_t | init, |

| lpf_spmd_t | spmd, | ||

| lpf_args_t | args | ||

| ) |

Runs the given spmd function from within an existing parallel environment as an SPMD program on a BSP computer. Effectively, a collective call takes the existing parallel environment and transforms it into a BSP computer. The mapping of processes (distinction between threads and processes is irrelevant in this context) is one-to-one and the args parameters will be passed on likewise. The type of supported `‘existing parallel environments’' is implementation dependent. The supported types are encapsulated as the init parameter. The reader is referred to the documentation of the implementation on how to obtain a valid lpf_init_t object.

- Thread safety

- Implementation defined. Obviously, a high-quality thread-based implementation requires complete thread safety. However, the implementor has more freedom when its implementation is process-based.

- Note

- The memory areas lpf_args_t.input and lpf_args_t.output must be allocated prior to a call to lpf_hook(), unless their respective sizes are 0.

- Neither lpf_exec(), lpf_hook(), nor lpf_rehook allocate any space for memory slots and message queues before executing the spmd function, which effectively means that a call to lpf_resize_memory_register() should always precede the first call to lpf_register_local() or lpf_register_global(), and that a call to lpf_resize_message_queue() should always precede the first call to lpf_put() or lpf_get() in the spmd function.

If _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY is defined, the call to the given spmd function will be made from the same memory address space as the current call to lpf_hook. If _LPF_EXCLUSIVE_MEMORY is defined instead, only the data passed through args will be guaranteed to be available when the call to the given spmd function is made.

- Note

- An implementation with _LPF_INCLUSIVE_MEMORY can thus be passed a lpf_t object from a second LPF implementation. Calls can then be mixed as long as the conditions on thread safety of the lpf_t are never violated.

- Parameters

-

[in] init A structure that allows multiple threads or processes in the top-layer parallelisation mechanism to communicate. The type of this parameter, as well as how to construct an instance of it, is implementation-defined. [in] spmd The entry point of the SPMD program. [in,out] args The input and output arguments this function has access to.

- Note

- The init parameter is necessarily implementation defined: an implementation of this API on top of PThreads would require a pointer to an initialisation struct that lives in shared-memory, an implementation based on TCP/IP would require addresses or sockets, while an MPI implementation would require communicators. A hybrid LPF implementation could even support multiple of these. For examples of such implementation-specific ways to retrieve an init object, see the LPF API extensions section.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When the requested LPF SPMD section was successfully started and has exited.

- LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY When the system could not start a new SPMD section due to memory allocation failures. A program may continue as though the call to this function was never made.

- LPF_ERR_FATAL When the LPF runtime encounters an unrecoverable error before, during, or after execution of the spmd function.

- Note

- On an LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY error, no ghost processes and no memory leaks are allowed. If an implementation cannot guarantee this, then the LPF_ERR_FATAL error code should be returned instead.

- A high quality implementation may make any data written to lpf_args_t.output by process 0 available to the calling process.

- BSP costs

- None (for the spmd function called, see The BSP cost model).

- Runtime costs

In addition to the total BSP cost and compute time required to execute the user-defined SPMD program, the overhead of calling lpf_hook at entry is \( \mathcal{O}( (a+b)g + l ) \), where \( g, l \) are the BSP machine parameters, and \( a, b \) equal the lpf_args_t.input_size and lpf_args_t.f_size fields of args, respectively.

Upon exit of the spmd function the overhead of this function is \( \mathcal{O}( cg + l ) \), where \( c \) equals the lpf_args_t.output_size field of args.

- Note

- If no process replication is employed, a good implementation achieves a total overhead of only \( \mathcal{O}(1) \).

-

Do not use the args I/O mechanism to transmit significant amounts of data; if this is required, consider using dedicated parallel I/O mechanisms. The lpf_args_t arguments are intended as a mechanism to pass program control flows, for instance, just like the C-style

argcandargv. - There are no added costs for argument I/O compared to lpf_exec, since this function has a separate lpf_args_t argument given for each process locally; i.e., the I/O via lpf_args_t is fully parallel using lpf_hook(). One case for communication of data in args is, like for the lpf_exec, when the implementation employs process replication.

- See also

- lpf_exec(),

- lpf_rehook().

- The BSP cost model.

◆ lpf_rehook()

| lpf_err_t lpf_rehook | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| lpf_spmd_t | spmd, | ||

| lpf_args_t | args | ||

| ) |

Runs the spmd function on the BSP computer but in a new fresh context. Message queues, memory registrations, etc. start all from scratch. This is useful when an interfacing with code that is not aware of the LPF context of the calling code: to achieve encapsulation. The process mapping is exactly the same as the parent context and memory is shared between parent and child. The call is collective for all participating processes.

- Thread safety

- Implementation defined. Obviously, a high-quality thread-based implementation requires complete thread safety. However, the implementor has more freedom when its implementation is process-based.

- Note

- The memory areas lpf_args_t.input and lpf_args_t.output must be allocated prior to a call to lpf_hook(), unless their respective sizes are 0.

- Neither lpf_exec(), lpf_hook(), nor lpf_rehook allocate any space for memory slots and message queues before executing the spmd function, which effectivly means that a call to lpf_resize_memory_register() should always precede the first call to lpf_register_local() or lpf_register_global(), and that a call to lpf_resize_message_queue() should always precede the first call to lpf_put() or lpf_get() in the spmd function.

- Parameters

-

[in] ctx The LPF context [in] spmd The entry point of the SPMD program. [in,out] args The input and output arguments this function has access to.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When the requested LPF SPMD section was successfully started and has exited.

- LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY When the system could not start a new SPMD section due to memory allocation failures. A program may continue as though the call to this function was never made.

- LPF_ERR_FATAL When the LPF runtime encounters an unrecoverable error before, during, or after execution of the spmd function.

- Note

- On an LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY error, no ghost processes and no memory leaks are allowed. If an implementation cannot guarantee this, then the LPF_ERR_FATAL error code should be returned instead.

- A high quality implementation may make any data written to lpf_args_t.output by process 0 available to the calling process.

- BSP costs

- None (for the spmd function called, see The BSP cost model).

- Runtime costs

- In addition to the total BSP cost and compute time required to execute the user-defined SPMD program, the overhead of calling lpf_hook is \( \mathcal{O}( 1 ) \).

- See also

- lpf_exec(),

- lpf_hook()

- The BSP cost model.

◆ lpf_register_global()

| lpf_err_t lpf_register_global | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| void * | pointer, | ||

| size_t | size, | ||

| lpf_memslot_t * | memslot | ||

| ) |

Registers a memory area globally. It assigns a global memory slot to the given memory area, thus preparing its use for inter-process communication.

This is a collective function, meaning that all processes call this primitive on a local memory area they own, in the same superstep, and in the same order. For registration of memory that is referenced only locally see lpf_register_local().

The registration process is necessary to enable Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) primitives, such as lpf_get() and lpf_put(); both source and destination memory areas are always indicated using registered memory slots that are returned by either this function or by lpf_register_local().

A successful call to this primitive takes effect after a subsequent call to lpf_sync(). Earlier use of the resulting memslot leads to undefined behaviour. A successful call immediately consumes one memslot capacity; see also lpf_resize_memory_register on how to ensure sufficient capacity.

- Note

- Registering a slot with zero size is valid. The resulting memory slot cannot be written to nor read from by remote LPF processes.

-

Passing

NULLas pointer and0for size is valid. - If all LPF processes register a zero-length memory area the registration slot is wasted but otherwise no error or undefined behaviour will occur.

- One registration consumes one memory slot from the pool of locally available memory slots, which must have been preallocated by lpf_resize_memory_register() or recycled by lpf_deregister(). Always use lpf_resize_memory_register() at the start of the SPMD function that is executed by lpf_exec(), since lpf_exec() itself does not preallocate slots.

- It is illegal to request more memory slots than have previously been registered with lpf_resize_memory_register(). There is no runtime check for this error, because a safe way out cannot be guaranteed without significant parallel error checking overhead.

- Global registration of memory areas is rather expensive. On platforms that support (R)DMA in hardware, the registered memory must be pinned into physical memory and their addresses communicated to all other nodes. Algorithm hotspots should hence be kept clear from registrations.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec(). [in] pointer The pointer to the memory area to register. [in] size The size of the memory area to register in bytes. [out] memslot Where to store the memory slot identifier.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS Successfully registered the memory region and successfully assigned a memory slot identifier.

- BSP costs

- This function may increase \( r_{c}^{(s)} \) and \( t_{c}^{(s)} \) by at most \( 2w(p-1) \) where \( w \) equals

sizeof(size_t)bytes and \( p \) equals the number of SPMD processes in this LPF run. See also The BSP cost model.

- Note

- Although there can be implementations that have no BSP costs associated to registration we do allow implementations that do require them.

- Runtime costs

- \( \mathcal{O}( \texttt{size} ) \).

- Note

- This asymptotic bound may be attained for implementations that require linear-time processing on the registered memory area, such as memory page pinning, to be able to guarantee good communication performance. If this is not required, a good implementation will require only \( \Theta(1) \) time.

On systems like Infiniband, handles to the remote memory areas must be communicated before they can be referred to. This can happen as part of a point-to-point synchronisation pattern during a lpf_sync().

◆ lpf_register_local()

| lpf_err_t lpf_register_local | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| void * | pointer, | ||

| size_t | size, | ||

| lpf_memslot_t * | memslot | ||

| ) |

Registers a memory area locally. It assigns to the memory area a local memory slot so that it can be used in inter-process communication that is initiated from the local process.

Contrary to lpf_register_global(), this primitive does not enable remote processes to access this memory.

Also contrary to lpf_register_local(), a successful local memory registration is immediate and does not require a subsequent call to lpf_sync(). A successful call also immediately consumer one memory slot capacity; see lpf_resize_memory_register() on how to ensure sufficient capacity.

The registration process is necessary to enable Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) primitives, such as lpf_get() and lpf_put(); both source and destination memory areas are always indicated using registered memory slots that are returned by either this function or by lpf_register_global().

- Note

- Registering a slot with zero size is valid, but may not be used to receive or send data.

-

Passing

NULLas pointer and0for size is also valid. - One registration consumes one memory slot from the pool of locally available memory slots, which must have been preallocated by lpf_resize_memory_register() or recycled by lpf_deregister(). Always use lpf_resize_memory_register() at the start of the SPMD function that is executed by lpf_exec(), since lpf_exec() itself does not preallocate slots.

- It is illegal to request more memory slots than have previously been registered with lpf_resize_memory_register(). There is no runtime check for this error, because a safe way out cannot be guaranteed without significant parallel error checking overhead.

- Local registration of memory areas may be expensive: some platforms may support remote memory access without registration but still require the memory area to be pinned in physical memory.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec(). [in] pointer The pointer to the memory area to register. [in] size The size of the memory area to register. [out] memslot Where to store the memory slot identifier.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS Successfully registered the memory region and successfully assigned a memory slot identifier.

- BSP costs

- None.

- Runtime costs

- \( \mathcal{O}( \texttt{size} ) \).

- Note

- This asymptotic bound may be attained for implementations that require linear-time processing on the registered memory area, such as memory page pinning, to be able to guarantee good communication performance. If this is not required, a good implementation will require only \( \Theta(1) \) time.

◆ lpf_deregister()

| lpf_err_t lpf_deregister | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| lpf_memslot_t | memslot | ||

| ) |

Deregisters a locally or globally registered memory area and puts the slot back into the pool of free memory slots.

For global memory slots this is a collective function, which means that all processes must call this function on the same global memory slots in the exact same order. For locally registered memory areas, the deregistration can be performed in any order.

Deregistration takes effect immediately. Any local or remote communication request using the given memslot in the current superstep is illegal.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec(). [in] memslot The memory slot identifier to de-register.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS Successfully deregistered the memory region.

- BSP costs

- None.

- Runtime costs

- \( \mathcal{O}(n) \), where \( n \) is the size of the memory region corresponding to memslot.

◆ lpf_put()

| lpf_err_t lpf_put | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| lpf_memslot_t | src_slot, | ||

| size_t | src_offset, | ||

| lpf_pid_t | dst_pid, | ||

| lpf_memslot_t | dst_slot, | ||

| size_t | dst_offset, | ||

| size_t | size, | ||

| lpf_msg_attr_t | attr | ||

| ) |

Copies contents of local memory into the memory of remote processes. This operation is guaranteed to be completed after a call to the next lpf_sync() exits. Until that time it occupies one entry in the operations queue. Concurrent reads or writes from or to the same memory area are allowed in a way resembling a CRCW PRAM with arbitrary conflict resolution. However, it is illegal to read from a memory location that is also being written.

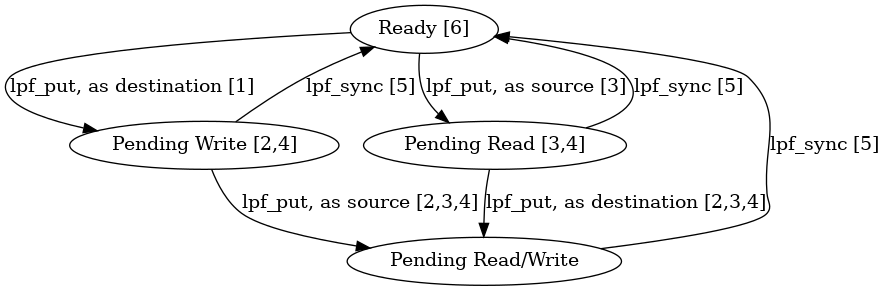

More precisely, usage is subject to the following rules:

- the destination memory area, which is uniquely identified by dst_pid, dst_slot, dst_offset, and size, enters a pending state.

- the destination memory area must be writeable during the time it is in a pending state.

- the source memory area, which is uniquely identified by src_slot, src_offset, size, must be readable during the time the destination memory area is in a pending state.

- the source and destination memory area must not be written to during computation phases as long as the destination area remains in a pending state.

- lpf_sync() completes the communication and changes all source memory areas and destination memory areas from a pending state into the ready state.

- If a destination memory area enters the ready state, the contents of that memory area must match that of any serialisation of all communication requests that have had non-empty overlap with the destination memory area during the time last time the memory area was in a pending state.

- A slot in the local message queue must have been reserved previously by lpf_resize_message_queue(). Note that lpf_exec() itself doesn't reserve any space for this.

- The above default behaviour may be adapted by use of the message handle msg. Any such behaviour-changing operations on msg are extensions to this specification.

Breaking any of the above rules results in undefined behaviour.

As illustration, below is given a small state diagram of a memory area annotated with rule numbers from the list above.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec() [in] src_slot The memory slot of the local source memory area registered using lpf_register_local() or lpf_register_global(). [in] src_offset The offset of reading out the source memory area, w.r.t. the base location of the registered area expressed in bytes. [in] dst_pid The process ID of the destination process [in] dst_slot The memory slot of the destination memory area at pid, registered using lpf_register_global(). [in] dst_offset The offset of writing to the destination memory area w.r.t. the base location of the registered area expressed in bytes. [in] size The number of bytes to copy from the source memory area to the destination memory area. [in] attr In case an attr not equal to LPF_MSG_DEFAULT is provided, the the message created by this function may have modified semantics that may be used to extend this API. Examples include:

- delaying the superstep deadline of delivery, and/or

- DRMA with message combining semantics.

These attributes are stored after a call to this function has completed and may be modified immediately after without affecting any messages already scheduled.

- Note

Possible operations that API extensions could provide via operations on message attributes of type lpf_msg_attr_t are, for instance,

- to explicitly allow or disallow communication overlap, or

- to allow communications to overlap with several calls to lpf_sync().

Such extensions are implementation-depenendent. Prescribing a specific behaviour in this specification would otherwise lead to a very specific type of BSP, while we aim for a most generic specification here.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When the communication request was recorded successfully.

- BSP costs

- This function will increase \( t_{c}^{(s)} \) and \( r_{c}^{(\mathit{pid})} \) by size, where c is the current superstep number and s is this process ID (as provided by lpf_exec)). See The BSP cost model on how this affects real-time communication costs.

- Runtime costs

- See The BSP cost model.

◆ lpf_get()

| lpf_err_t lpf_get | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| lpf_pid_t | src_pid, | ||

| lpf_memslot_t | src_slot, | ||

| size_t | src_offset, | ||

| lpf_memslot_t | dst_slot, | ||

| size_t | dst_offset, | ||

| size_t | size, | ||

| lpf_msg_attr_t | attr | ||

| ) |

Copies contents from remote memory to local memory. This operation completes after one call to lpf_sync(). Until that time it occupies one entry in the operations queue. Concurrent reads or writes from or to the same memory area are allowed in a way resembling a CRCW PRAM with arbitrary conflict resolution. However, it is illegal to read from a memory location that is is also being written.

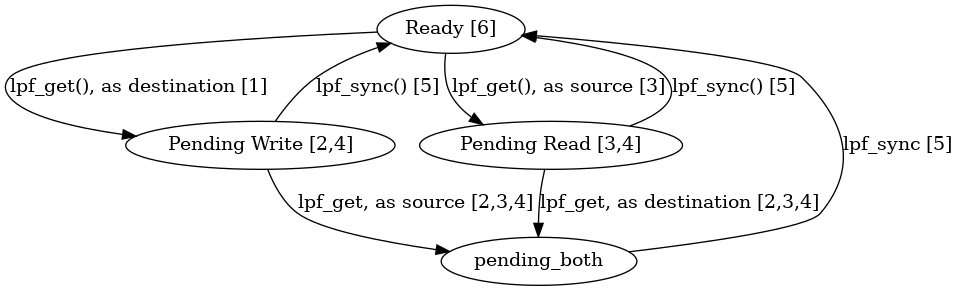

More precisely, Usage is subject to the following rules:

- the destination memory area, which is uniquely identified by dst_slot, dst_offset, and size, enters a pending state.

- the destination memory area must be writeable during the time it is in a pending state.

- the source memory area, which is uniquely identified by src_pid, src_slot, src_offset, and size, must be readable during the time the destination memory area is in a pending state.

- the source and destination memory area will not be written to during computation phases as long as the destination area remains in a pending state.

- lpf_sync() completes the communication and changes all source memory areas and destination memory areas from a pending state into the ready state.

- If a destination memory area enters the ready state, the contents of that memory area must match that of any serialisation of all communication requests that have had non-empty overlap with the destination memory area during the time last time the memory area was in a pending state.

- A slot in the local message queue must have been reserved previously by lpf_resize_message_queue(). Note that lpf_exec() itself doesn't reserve any space for this.

- The above default behaviour may be adapted by use of the message handle msg. Any such behaviour-changing operations on msg are extensions to this specification.

Breaking any of the above rules results in undefined behaviour.

As illustration, below is given a small state diagram of a memory area annotated with rule numbers from the list above.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec(). [in] src_pid The process ID of the source process. [in] src_slot The memory slot of the source memory area at pid, as globally registered with lpf_register_global(). [in] src_offset The offset of reading out the source memory area, w.r.t. the base location of the registered area expressed in bytes. [in] dst_slot The memory slot of the local destination memory area registered using lpf_register_local() or lpf_register_global(). [in] dst_offset The offset of writing to the destination memory area w.r.t. the base location of the registered area expressed in bytes. [in] size The number of bytes to copy from the source remote memory location. [in] attr In case an attr not equal to LPF_MSG_DEFAULT is provided, the the message created by this function may have modified semantics that may be used to extend this API. Examples include:

- delaying the superstep deadline of delivery, and/or

- DRMA with message combining semantics.

These attributes are stored after a call to this function has completed and may be modified immediately after without affecting any messages already scheduled.

- Note

- Possible operations that API extensions could provide via operations on message attributes of type lpf_msg_attr_t are, for instance,

- to explicitly allow or disallow communication overlap, or

- to allow communications to overlap with several calls to lpf_sync(). Such extensions are implementation-depenendent. Prescribing a specific behaviour in this specification would otherwise lead to a very specific type of BSP, while we aim for a most generic specification here.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When the communication request was recorded successfully.

- BSP costs

- This function will increase \( r_{c}^{(s)} \) and \( t_{c}^{(\mathit{pid})} \) by size, where c is the current superstep number and s is this process ID (as provided via lpf_exec(). See The BSP cost model on how this affects real-time communication costs.

- Runtime costs

- See The BSP cost model.

◆ lpf_sync()

| lpf_err_t lpf_sync | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| lpf_sync_attr_t | attr | ||

| ) |

Terminate the current computation phase, then execute all globally pending communication requests. The local part of the global communication phase is guaranteed to have finished at exit of this function after which the next computation phase starts.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec() [in] attr Any additional hints the user can provide the runtime with in hopes of speeding up the synchronisation process beyond what is predicted by the BSP cost model. An implementation must always adhere to the BSP cost contract no matter what hints the lpf_sync() is provided with. The default, and only possible lpf_sync_attr_t defined by this specification is the LPF_SYNC_DEFAULT. Any other attributes are extensions to this API.

- Note

- The attribute can, for instance, be used to incorporate zero-cost synchronisation features into the LPF implementation.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When all operations were executed successfully. This is not a guarantee that all processes were able to maintain performance contracts.

- LPF_ERR_FATAL When another process has already returned from the spmd function, or when the library has encountered another unrecoverable error.

- Note

- If one process encounters an unrecoverable error it may mean that the normal communication channels may be unusable. Therefore it cannot be guaranteed that all processes are notified at the same call to lpf_sync(). It is guaranteed however that lpf_sync() calls will not deadlock and that the calling lpf_exec() returns LPF_ERR_FATAL.

- BSP costs

- See The BSP cost model. A call to this function does not change any of the cost variables \( r_c^{(s)}, t_c^{(s)} \).

- Runtime costs

- See The BSP cost model.

◆ lpf_probe()

| lpf_err_t lpf_probe | ( | lpf_t | ctx, |

| lpf_machine_t * | params | ||

| ) |

This primitive allows a user to inspect the machine that this LPF program has been assigned. All resources reported in the lpf_machine_t struct are under full control of the current instance of the LPF implementation for the lifetime of the supplied ctx parameter.

A call to this function with the ctx parameter equal to LPF_ROOT will yield full information on the entire machine assigned to the LPF implementation. Within an LPF SPMD section, each process is assigned a subset of the available resources. Information on that subset may be enquired using the lpf_t pointer returned by the lpf_exec() of interest.

- Parameters

-

[in] ctx The currently active runtime state as provided by a top-level lpf_exec(). Outside an SPMD section, LPF_ROOT may be used if there is a master LPF process. [out] params The BSP machine parameters

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS when the machine was successfully probed.

- LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY when the probe failed due to memory allocation failures. The current call failed but this does not have side effects; programs can proceed as though this call never was made.

- Runtime costs

- Implementation defined. Probing a machine is potentially costly, so use it sparingly.

- Note

- An implementation may define a high-peformance \( \Theta(1) \) function to, e.g., facilitate user-defined actions based on performance, power, or temperature envelopes.

◆ lpf_resize_memory_register()

Resizes the memory register for subsequent supersteps.

The new capacity becomes valid after a next call to lpf_sync().

Each local (lpf_register_local()) or global (lpf_register_global()) registration counts as one.

The local process allocates enough resources to register up to max_regs memory regions. This is a purely local property and does not guarantee that other processes have the same capacity; indeed, different processes may require different memory slot capacities, which LPF allows. Since the programmer can always determine a suitable upper bound for the number of registrations when designing her algorithm, there are no runtime out-of-bounds checks prescribed for lpf_register_local() and lpf_register_global()– this would also be too costly as error checking would require communication.

If memory allocation was successful, the return value is LPF_SUCCESS and the local process may assume the new buffer size max_regs. In the case of insufficient local memory the return value will be LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY. In that case, it is as if the call never happened and the user may retry the call locally after freeing up unused resources. Should retrying not lead to a successful call, the programmer may opt to broadcast the error (using existing slots) or to give up by returning from the spmd section.

- Note

- lpf_exec() nor lpf_hook() reserve any space, which effectively means that a call to lpf_resize_memory_register(), lpf_resize_message_queue(), and lpf_sync() should always precede the first call to lpf_register_local(), lpf_register_global(), lpf_put(), or lpf_get().

- The current maximum cannot be retrieved from the runtime. Instead, the programmer must track this information herself. To provide encapsulation, please see the lpf_rehook().

- When the given memory register capacity is smaller than the current capacity, the runtime is allowed but not required to release the allocated memory. Such a call will always be successful and return LPF_SUCCESS.

- This means that an implementation that allows shrinking the given capacity must also ensure the old buffer remains intact in case there is not enough memory to allocate a smaller one.

- The last invocation of lpf_resize_memory_register() determines the maximum communication pattern in the subsequent supersteps.

- When the first call to lpf_resize_memory_register() fails, the sensible and only way out of an spmd section is to return from it since there is no way to communicate to other processes. Since the call may have succeeded on other processes and could continue to the next lpf_sync(), it is likely that the SPMD section will return with LPF_ERR_FATAL.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec(). [in] max_regs The requested maximum number of memory regions that can be registered. This value must be the same on all processes.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When this process successfully acquires the resources.

- LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY When there was not enough memory left on the heap. In this case the effect is the same as when this call did not occur at all.

- BSP costs

- None

See also The BSP cost model.

- Runtime costs

- \( \Theta( \mathit{max\_regs} ) \).

- Rationale

- To design the interface for this functionality many boundary conditions need to be considered, e.g.:

- Memory registrations may require other resources other than memory. This can be a scarce resource. For example, an MPI implementation may only allow a few thousand windows.

- LPF should be extendable. Extensions could be foreseen that require more resources but with other parameters. For example, an extension could provide buffered communication in which case it is also necessary to allocate buffer space for the message payloads. An extensible naming system is therefore important.

- An out-of-memory error should be returned ASAP and mitigable .

- Communication costs must be kept low. Negotiating message buffer sizes globally and error checking can get very expensive, because in those cases an all-gather of the buffer sizes is required.

- Implementation Hints

- The semantics of this functions restrict the choice of data-structures in a scalable implementation to:

- For the memory register, each process has a two ID generators. One of them creates the same sequence of IDs on all processes, which can be used to register memory areas globally. The other ID generator is used for local memory registration. Either registration is stored in a slot in a preallocated array as a tuple with the ID, the pointer to the memory area and its size, and a boolean value whether it is global or local registration. By careful generation of IDs the mapping from ID to slot can be kept fast and simple.

◆ lpf_resize_message_queue()

Resizes the message queue to support the specified maximum communication pattern during subsequent supersteps.

The local process allocates enough resources to support patterns of up to max_msgs messages, but that does not guarantee that others have. All processes may therefore only assume that the global minimum of max_msgs messages will be reserved. Each call to lpf_put() or lpf_get() counts as one message on the originating process and as one message on the target process, which may be itself. Since the programmer can always determine a suitable upper bound for the maximum communication pattern when designing her algorithm, there are no runtime out-of-bounds checks prescribed for lpf_get() and lpf_put().

If memory allocation was locally successful, the return value is LPF_SUCCESS. However, in case of insufficient memory the return value will be LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY on one or more processes. In that case, it is as if the call never happened. However, the failing processes may retry the call locally after freeing up unused resources – it is implementation defined what helps – and on success all processes may assume the new global minimum as buffer size. If the problem persists it is up to the programmer to mitigate this problem globally by broadcasting the error or to give up by returning from the spmd section.

- Note

- lpf_exec() nor lpf_hook() reserve any space, which effectively means that a call to lpf_resize_memory_register(), lpf_resize_message_queue(), and lpf_sync() should always precede the first call to lpf_register_local(), lpf_register_global(), lpf_put(), or lpf_get().

- The current maximum cannot be retrieved from the runtime. Instead, the programmer must track this information herself. To provide encapsulation, please see the lpf_rehook().

- When the given maximum communication pattern is smaller than the previously given maximum, the runtime is allowed but not required to release the allocated memory to the system memory pool. Furthermore, such a call will always be successful and return LPF_SUCCESS.

- This means that an implementation that allows shrinking the given capacity must also ensure the old buffer remains intact in case there is not enough memory to allocate a smaller one.

- The last invocation of lpf_resize_message_queue() determines the maximum communication pattern in the subsequent supersteps.

- When the first call to lpf_resize_message_queue() fails, the sensible and only way out of an spmd section is to return from it, since there is no way to communicate to other processes. Since the call may have succeeded on other processes, so that they could continue to the next lpf_sync(), it is likely that the library enters a failure state and lpf_exec() will return LPF_ERR_FATAL.

- Thread safety

- This function is safe to be called from different LPF processes only. Any further thread safety may be guaranteed by the implementation, but is not specified. Similar conditions hold for all LPF primitives that take an argument of type lpf_t; see lpf_t for more information.

- Parameters

-

[in,out] ctx The runtime state as provided by lpf_exec(). [in] max_msgs The requested maximum accepted number of messages per process. This value must be the same on all processes.

- Returns

- LPF_SUCCESS When this process successfully acquires the resources.

- LPF_ERR_OUT_OF_MEMORY When there was not enough memory left on the heap. In this case the effect is the same as when this call did not occur at all.

- BSP costs

- None

See also The BSP cost model.

- Runtime costs

- \( \Theta( \mathit{max\_msgs} ) \).

- Rationale

- To design the interface for this functionality many boundary conditions need to be considered, e.g.:

- Scheduling communication requires memory, which may be a scarce resource. When the runtime knows what the largest communication can be, it can reserve memory more conservatively.

- An out-of-memory error should be returned ASAP and mitigable.

- Communication costs must be kept low. Negotiating message buffer sizes globally and error checking can get very expensive, because in those cases an all-gather of the buffer sizes is required.

- If message delays are used, then the information how large message buffers need to be is already available. However, this should not be used to reallocate buffers, because that would cause performance anomalies and would require collective communication to update the reallocated addresses on remote processes.

- Many DRMA hardware/MPI implementations don't guarantee how overlapping writes are ordered. On those platform the lpf_sync() will have to do an initial round to adjust write address ranges, for which it will be required to do an all-to-all with small messages. However, a straightforward all-to-all requires O(p) memory and messages which is too much. An all-to-all using recursive doubling requires only O(h_max) but on all processes. Therefore the message buffer size must be a global value.

Variable Documentation

◆ lpf_pid_t

| typedef lpf_pid_t |

An unsigned integral type large enough to hold the number of processes. All operations that work with C unsigned integral types also work for this type.

- Communication

- It is safe to communicate values of this type.

◆ LPF_NO_ARGS

|

extern |

An empty argument that can be passed to lpf_exec() when no input or output is required. It has the lpf_args_t data fields lpf_args_t.input, lpf_args_t.output, and lpf_args_t.f_symbols set to NULL. The lpf_args_t size fields lpf_args_t.input_size, lpf_args_t.output_size, and lpf_args_t.f_size are set to 0.

An implementation thus must implement LPF_NO_ARGS as

- Note

- Real-world applications will likely always require initial program parameters to be passed into the parallel SPMD section.

◆ lpf_err_t

| typedef lpf_err_t |

Type to hold an error return code that functions can return.

An implementation must ensure the error codes of this type may be compared for equality or for inequality.

- Communication

- It is safe to communicate values of this type. An implementation must ensure this.

◆ lpf_init_t

| typedef lpf_init_t |

Represents a minimal form of initialisation data that can be used to to lpf_hook() an LPF SPMD section from an existing, possibly non-bulk synchronous, parallel environment. In particular, this object will be able to bootstrap communications between processes. How such an object can be obtained, depends on the implementation.

- Communication

- Object of this type must never be communicated.

◆ lpf_sync_attr_t

| typedef lpf_sync_attr_t |

A mechanism to provide hints to the global lpf_sync() operator. Through this type, information may be made available to the LPF runtime that will allow it to speed up the synchronisation process. The attribute that shall induce the default behaviour shall be LPF_SYNC_DEFAULT.

The maximum BSP costs, as defined in the section The BSP cost model, shall remain to define an upper limit in execution.

Any call to lpf_sync using a modified lpf_sync_attr_t, shall not modify the semantics of RDMA communication using lpf_get or lpf_put using the default message attribute LPF_MSG_DEFAULT.

- Communication

- Object of this type must not be communicated.

◆ lpf_memslot_t

| typedef lpf_memslot_t |

Type to identify a registered memory region. Both source and destination memory areas must be registered for direct remote memory access (DRMA).

- Communication

- Object of this type must not be communicated.

◆ lpf_msg_attr_t

| typedef lpf_msg_attr_t |

A mechanism to provide properties to messages scheduled via lpf_put and lpf_get. This information may allow for LPF implementations to change the functional and/or performance semantics of the message to be sent; for instance, to allow for a delay in delivery of a message, or to instruct the runtime that the message should be combined with data already residing in the destination memory, e.g., by addition.

- Communication

- Objects of this type must not be communicated.

◆ LPF_NONE

|

extern |

◆ LPF_ROOT

|

extern |

The context of the master process of the assigned machine. This notion of a master process is not guaranteed for all implementations; the user is advised to consult the implementation's manual, because, in case of absence, the value of LPF_ROOT is undefined. Implementations that do not define LPF_ROOT must provide a mechanism to retrieve a valid instance of lpf_init_t– using such an instance, an LPF SPMD section can still be started using lpf_hook().

There shall only be one LPF process (one thread or one process) in any implementation that provides a valid LPF_ROOT.

- Communication

- This value must not be communicated.

◆ LPF_INIT_NONE

|

extern |

An invalid lpf_init_t object.

- Communication

- This value must not be communicated.

◆ LPF_SYNC_DEFAULT

|

extern |

Apply the default syncing mechanism in lpf_sync().

- Communication

- This value must not be communicated.

◆ LPF_MSG_DEFAULT

|

extern |

◆ LPF_MAX_P

|

extern |

The maximum value that a variable of type lpf_pid_t can store. This can come in useful when you want to run an spmd function on the maximum number of processors with lpf_exec(). In that case, use NULL as parameter for the args parameter.

◆ LPF_INVALID_MACHINE

|

extern |

A dummy value to initialize an abstract machine of type lpf_machine_t at their declaration.

◆ LPF_INVALID_MEMSLOT

|

extern |

A dummy value to initialize memory slots at their declaration. A debug implementation may check for this value so that errors can be detected.